There are six interpretation panels located along the boulevard, highlighting the history and cultural heritage of the area. Below are the inscriptions from each panel.

Activism Panel Inscription

Liverpool 8, the traditional home of the city’s black and racial minority communities for over 100 years, has a long and proud history of political activism, resisting social injustice from the local to the global. Between 1980 and 1981 a wave of uprisings swept inner city areas across the UK in anger at the racist and brutal policing of black communities, social inequalities and entrenched institutional discrimination. In Liverpool, where racism was described by Lord Gifford as ‘uniquely horrific’, battles between the police and both black and white youth, raged for nine days in the longest of the civil disturbances. On the second day, the Liverpool 8 Defence Committee was formed with a mandate to monitor police behaviour, to offer support to those arrested and imprisoned, and assess the decisions of the judiciary. Just one year later, members of that committee had established the Liverpool 8 Law Centre in two Victorian mansions at 34-36 Princes Road. The Law Centre was a vital community service, providing free legal advice and representation, an Access to Law programme, a reference library and leadership in local, national and international campaigns.

34-36 Princes Road also became home to Liverpool Black Sisters which was renamed around 1979 from the Liverpool Black Women’s Group and was part of a national network. They campaigned on issues affecting women in their community and provided child-care and afterschool services, allowing local women to access employment and education. From the basement of the Law Centre they dreamt of developing their own building. The Kuumba Imani Millennium Centre, which opened in 2004, grew out of that dream. Merseyside Immigration Advice Unit (MIAU) was also housed within and supported by the Law Centre. Established in 1988, MIAU was a response to increasingly repressive immigration controls.

In the face of acute racism within the education system Elimu Wa Nane was established in 1979 in the Methodist Centre, providing afterschool activities to meet the needs of young learners from Liverpool 8. Between 1994 and 1998 the renamed Elimu Study School operated from Streatlam Tower as an alternative to mainstream secondary education.

These organisations, housed on Princes Boulevard, evolved from a long involvement in the struggle for racial equality by Liverpool’s black communities. They followed such organisations as the League of Coloured People which formed in 1920 following anti-black race riots that erupted in British seaports in 1919 and the Colonial Defence Committee, formed to raise legal defence funds following further anti-black rioting in 1948.

The Boulevard has been the site of protest in defence of local communities and peoples across the globe, hosting countless demonstrations such as those campaigning for safe crossings to those that stood in solidarity with the people of South Africa against the Apartheid regime.

Gratitude is owed to all those activists who came before us as we continue to strive for equality and justice.

Faiths Panel Inscription

Princes Boulevard is at the centre of a vibrant multi-faith community where people of different national origins, religions and spiritual beliefs have lived together since the mid-Nineteenth Century. The many places of worship both on and surrounding the Boulevard reflect the historic and continued cultural diversity of this Victorian thoroughfare.

The Greek Orthodox Church of St Nicholas was built in 1870 in the neo-Byzantine architecture style. The building was designed by architects W&J Hay and the building overseen by Henry Sumners. The construction was funded by Greek merchants who had settled in Liverpool. It is an enlarged version of St Theodore’s Church in Constantinople.

St Margaret of Antioch is an Anglican parish church. Built in 1869, it was designed in gothic style by GE Street and funded by a local stockbroker. In 1926 the Jesus Chapel, designed by Hubert B Adderley, was added to the north of the church. The Lady Chapel contains a dedication to HMS Lively, a Royal Navy destroyer built at Cammell Lairds and adopted by the church in 1947. A scroll contains the names of those who lost their lives when the ship was sunk during the Second World War.

Princes Road Synagogue is home to the Liverpool Old Hebrew Congregation, the oldest Jewish congregation in the city, with a history intertwined with that of the wider Jewish community in Liverpool. It was designed by W&G Audsley, two brothers from Edinburgh who had no previous experience of building synagogues. It was consecrated on 2 September 1874. At that time the Jewish community in Liverpool was the second largest in the UK, after London. The synagogue is one of the finest examples of the Moorish Revival style architecture in British synagogues and received Grade I listing in 2014.

Our Lady of Mount Carmel and St Patrick Catholic Parish Churches are both located just a short walk away from the Boulevard. St Patrick’s neoclassical style architecture was designed by John Slater and completed in 1827. The free-standing statue of Saint Patrick on the outside of the building was moved from the St Patrick Insurance Company building in Dublin in 1827. Our Lady of Mount Carmel was built in 1876-78 by the noted Liverpool architect James O’Byrne.

The Welsh Presbyterian Church, designed by W&G Audsley, also the architects of Princes Road Synagogue, was completed in 1867. Then it was the highest building in Liverpool and because of its tall steeple it was nicknamed the ‘Welsh Cathedral’ or ‘Toxteth Cathedral’. It served the large Welsh community; an estimated 120,000 Welsh people migrated to Liverpool between 1851 and 1911. Many were employed as builders and are responsible for the construction of whole sections of Liverpool’s terraced housing including the famous ‘Welsh Streets’ off Princes Road. In 1982 it was sold to the Brotherhood of the Cross and Star, a Nigerian religious organisation. In the 1990s it was vacated and became derelict. A redevelopment of the building as an environmental centre for children, families and the local community is planned.

Al-Rahma Mosque is located close to the Boulevard on the corner of Hatherley and Mulgrave Street. It was built in 1974 by the Liverpool Muslim Society which was founded in 1953. Previously the Mosque operated from a private home on Cairns Street. The first floor, the school and the Imam’s accommodation were added in 1979. To accommodate a growing Muslim population, redevelopment was undertaken, funded entirely by donations from the Muslim community and completed in 2008. Replacing the basic building, the Al-Rama Mosque, designed by G Squared, has a traditional golden dome, crescent and minarets.

Mount Zion Wesleyan Methodist Church was situated on Princes Road between Eversley and Mulgrave Streets. It was erected in 1880. It later became a Chinese Methodist Church but was demolished in 1973 after a fire.

Princes Park Methodist Church opened in 1969. A prominent feature is the sculpture of the ‘Resurrection of Christ’ by renowned Liverpool artist Arthur Dooley, which created some controversy when it was unveiled. The 12ft black metal statue with facial features that seemed to combine many ethnicities, broke all conventional ideas of what Jesus would have looked like. Known locally as the ‘The Black Christ’, the statue has become a much-loved feature of the area.

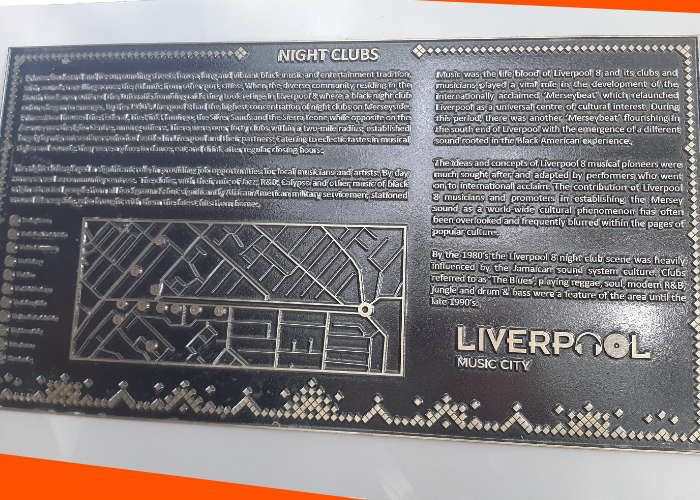

Night Clubs Panel Inscription

Princes Boulevard and its surrounding streets have a long and vibrant black music and entertainment tradition, with sounds travelling across the Atlantic from other port cities. When the diverse community residing in the South Dock area suffered the Luftwaffe bombing raids they took refuge in Liverpool 8 where a black night club culture began to emerge. By the 1950s Liverpool 8 had the highest concentration of night clubs on Merseyside. Princes Road housed the Federal, The Pink Flamingo, the Silver Sands and the Sierra Leone while opposite on the Avenue was the Igbo Centre, among others. There were over forty clubs within a two-mile radius, established largely by migrant seafarers who had settled in Liverpool and their partners. Catering to eclectic tastes in musical styles and sounds, they were a place to dance, eat and drink after regular closing hours. The night clubs played a significant role in providing job opportunities for local musicians and artists. By day some served as community centres. The clubs, with their mix of Jazz, R&B, Calypso and other music of black origin attracted people from all backgrounds but significantly African American military servicemen, stationed around Merseyside, who brought with them the latest hits from home.

Music was the life blood of Liverpool 8 and its clubs and musicians played a vital role in the development of the internationally acclaimed ‘Merseybeat’ which relaunched Liverpool as a universal centre of cultural interest. During this period, there was another ‘Merseybeat’ flourishing in the south end of Liverpool with the emergence of a different sound rooted in the Black American experience. The ideas and concepts of Liverpool 8 musical pioneers were much sought after and adapted by performers who went on to international acclaim. The contribution of Liverpool 8 musicians and promoters in establishing the Mersey sound as a world-wide cultural phenomenon has often been overlooked and frequently blurred within the pages of popular culture. By the 1980’s the Liverpool 8 night club scene was heavily influenced by the Jamaican sound system culture. Clubs referred to as ‘The Blues’, playing reggae, soul, modern R&B, jungle and drum & bass were a feature of the area until the late 1990s.

History Panel Inscription

Princes Boulevard is a unique example of formal planning on a large scale in Nineteenth Century Liverpool, forming part of the setting for Princes Park which was designed by Joseph Paxton in 1842 as a private development for Richard Vaughan Yates. The grand mansions, with gothic and classical influences were built for the merchant and commercial classes, whose considerable wealth came from shipping and trade. At this time the port of Liverpool was pivotal within global commerce, due to its prior involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

From its inception the Boulevard had far reaching international connections. In 1890 the first dedicated museum of Japanese art was opened in the grounds of Streatlam Tower by James Lord Bowes, wool merchant and art philanthropist, who commissioned the building in 1872, designed by W&G Audsley. In 1891 Bowes hosted a Japanese ‘fancy fair’ in the museum, attracting 20,000 people over six days. But the Boulevard was more than just a playground for the rich. In 1886 the newly formed Liverpool Adult Deaf and Dumb Benevolent Society received a 2000-year lease from Lord Sefton for land on Princes Avenue and Parkway. In 1887 The Liverpool Adult Deaf and Dumb Institute, with lecture hall and chapel, was formally opened by H.R.H Princess Louise. In the 1980s the building was taken over by The Igbo Community Association. In 1900, at 1 Princes Road, a nursing establishment was built by the David Lewis Trust for Liverpool Queen Victoria District Nursing Association ‘to promote the completion in this city of the system of nursing the poor in their own homes’. Built into its boundary wall is a Florence Nightingale Memorial, erected in 1913, containing a sculpture by CJ Allen.

After the First World War the character of the Boulevard began to change. The wealthy, and to some extent the middle classes, began to leave for the suburbs, vacating huge houses that could be split into flats and rooms that were ripe for multiple occupation. Around this time the more diverse community from the Southern Dock area, largely formed by black and migrant seafaring families, began to move up the hill to Liverpool 8. This movement was accelerated when the area around Pitt Street and Upper Frederick Street was heavily bombed during the Second World War. Successive waves of immigration in the post war period led to further settlement in the area around Princes Boulevard adding to its rich cultural mix.

L8 Garden Panel Inscription

The original ‘8’ sculpture, designed by local children, symbolises the spirit and journeys of the people of Liverpool 8. The links of the 8 represent the chain connecting a ship to its anchor. The sculpture is a reflection on the maritime heritage of our local community, which was shaped by merchant seafarers from across the globe, particularly West Africa, China and East Asia, South Asia, the Caribbean, Somalia and Yemen. They came as single men and some chose to remain, even during the hardest of times. Often, they married and settled with local women, many of them Irish, and had extended and diverse families. The area’s relationship to the sea has created a community where culture is shared and creativity flows.

The new ‘L8’ sculpture composition is the result of engagement with the local residents and community groups. It comprises a new granite ‘L’ etched with 1800’s Liverpool 8 map and a series of granite blocks with phrases to expand on the original ‘8’ sculpture in the telling of the migration from Liverpool Docks to Liverpool 8.

The Huskisson plinth, which once celebrated the Victorian MP William Huskisson. It has been empty since 1982. The reasons for this have been acknowledged with a new inscription acknowledging his role in the slave trade.

Huskisson Panel Inscription

William Huskisson 1770-1830 whose statue once stood on this plinth was MP for Liverpool from 1823 to his death in 1830. He first entered parliament in 1796 and as MP for Liskeard voted for the abolition of the slave trade in 1807. During his time representing Liverpool many of his supporters in the town were plantation owners and were not in favour of an end to slavery in Britain’s colonies. These pro-planter sentiments led Huskisson to oppose the abolition of slavery; and in 1826, rather than support calls for immediate abolition, Huskisson championed the passing of the Consolidated Slave Law, introduced as a compromise between those agitating for the abolition of slavery and the planters who wanted to maintain it. Huskisson did not live to see the abolition, he was killed on the 15th September 1830 whilst attending the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Slavery was finally abolished by the British in 1834.

In the early hours of July 22, 1982, the statue was removed from the plinth by a group of activists offended at Huskisson’s role in supporting slavery.